The various kinds of food that modern society has brought us often makes us eat more than our bodies need and can handle, leading to obesity and various other metabolic diseases. In fact, spending on metabolic diseases has become a major social health and welfare expense. As the body's command, how our brain regulates eating, why we eat, why we don't eat, and how much we eat, these are questions that are increasingly receivinggetting our attention.

Past studies have shown that the mammal’s hypothalamus is the main brain region involved in the regulation of feeding. Early clinical cases showed that patients with a lesion of lateral hypothalamus often suffer from loss of appetite or even anorexia (1, 2). Further animal studies confirmed that the lateral hypothalamus is indeed an important region in the regulation of eatingfeeding (3, 4). With the cloning of the obesity-related gene AgRP (Agouti-related protein) (5), the arcuate nucleus at the base of the hypothalamus and the AgRP-positive neurons therein have been identified as the critical mechanisms in the eatingfeeding regulation (6, 7). Mice with damaged AgRP-positive neurons in the arcuate nucleus will even starve themselves to death (8). Is there another brain region in the hypothalamus that regulates feeding independent of the lateral hypothalamus and the arcuate nucleus?

An article published in Science last year revealed an important role of the zona incerta in binge eating (9). A research team led by Dr. Fu Yu’s, an alumnus of Class of 1998 of Kuang Yaming Honors School who currently works withat the Agency for Science, Technology and Research in Singapore (A*STAR), reports the important role of another hypothalamic nucleus, the tuberal nucleus (TN), in mice in the feeding regulation suggesting previously unknown mechanism of feeding regulation.

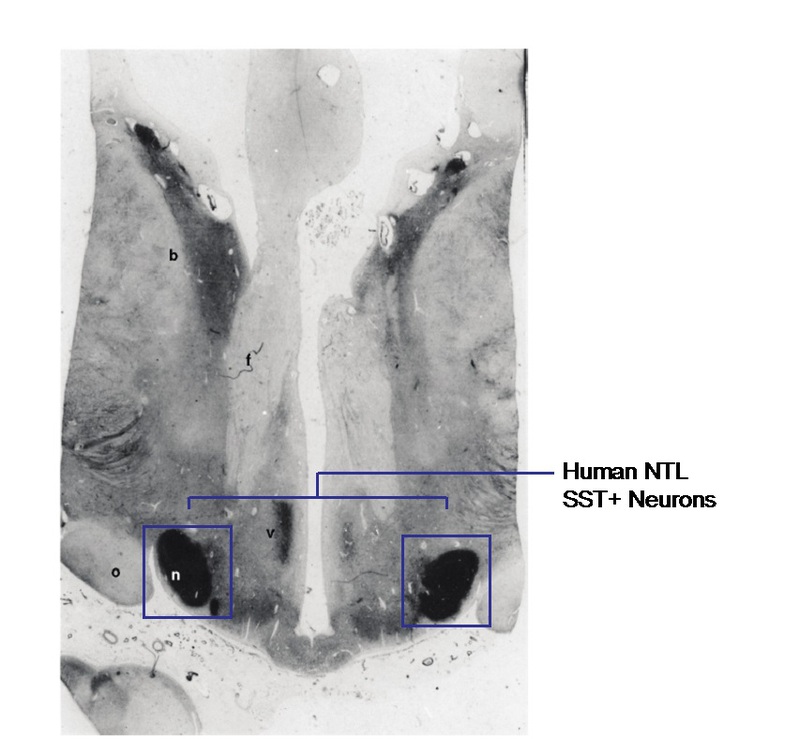

Lateral tuberal nucleus, as known as nucleus tuberalis lateralis (NTL), in human hypothalamus is a special structure in the brain (Figure 1). Although this brain region was listed in a manual about hypothalamus published as early as in 1938 (10), its function remained unknown until this issue of Science. This brain region has long been thought to be unique to human and primates. Even though the mouse has TN, it has never been clearly established whether this is the homologous brain region of the human NTL (11). The physiological function of the human NTL is unknown, but in various neurodegenerative disorders, such as Huntington's disease, specific pathological changes in the NTL have been identified (e.g., a significant decrease in the number of positive cells of the somatostatin, SST) (12, 13), but what exactly the consequences of the pathological changes at the NTL is still an open question. Deep hypothalamic lesions that probably went into the NTL in human patients have led to hypophagia, and NTL pathology has been correlated with feeding and metabolic regulation.

Fig. 1. SST-positive neurons at the NTL of hypothalamus (modified from Timmers et al. 1996)

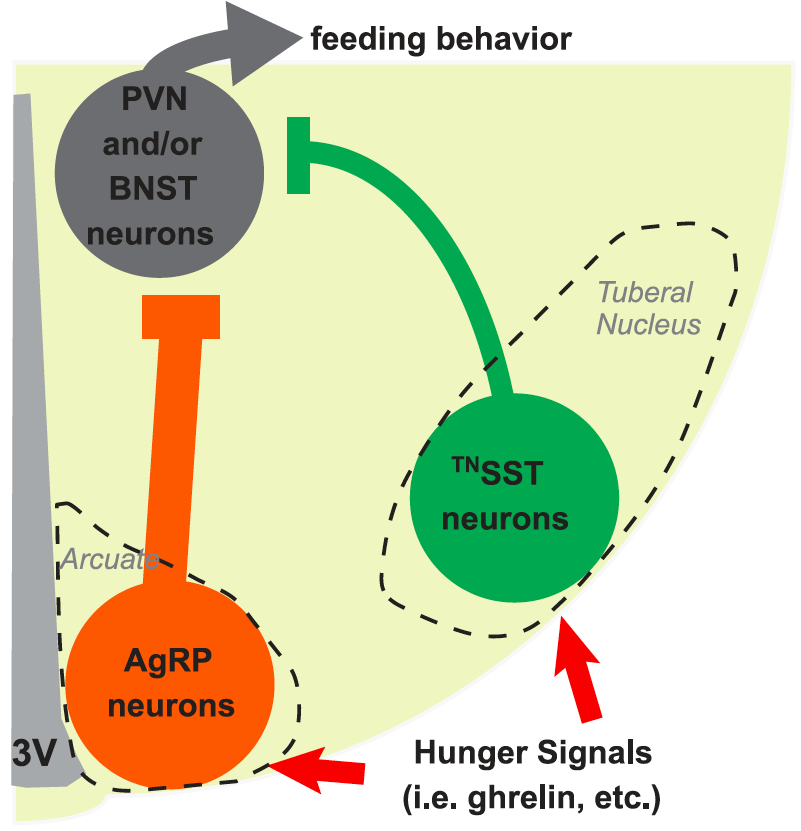

In this issue of Science, by using gene engineered mice specifically marked with somatostatin (SST)-positive neurons, Dr. Yu Fu’s team found the presence of a dense cluster of SST-positive neurons similar to human NTL in the hypothalamic tuberal nucleus of mice, giving strong support that the TN of mice is a homologous brain region of human NTL. For the first time, the team found GABAergic SST-positive neurons in the TN haDhad an important role in feeding regulation (Figure 2). GABAergic tuberal SST (TNSST) neurons were activated by hunger and by the hunger hormone. Activated TNSST neurons effectively promote feeding of mice by optogenetic and chemogenetic means, while inhibition of TNSST neurons reduces feeding. TNSST neurons regulate feeding mainly via projections to the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN) and the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST). The team also found that eliminating TNSST neurons not only reduced food intake, but also reduced weight growth.

Fig. 2. Patterns of SST-positive neuronal cells promoting feeding in the in the mouse TN

The important implications of this study are: (1) confirming the existence of homologous structures of human NTL in mouse; (2) revealing for the first time the physiological function of the mouse TN, while suggesting the physiological function of the human NTL; (3) revealing a previously unknown mechanism of feeding regulation; and (4) promising a new understanding of metabolic or appetite changes in patients with neurodegenerative diseases, which may better improve the life quality of these patients.

Co-first authorship of the paper is shared by Sarah Luo, a post-doc researcher of Laboratory of Yu Fu, A*STAR, Singapore, Huang Ju, a research fellow of School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, and Li Qin, an associate research fellow of Wuhan Institute of Physics and Mathematics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Wuhan. The research was completed under the supervision of Dr. Fu Yu.

Full text:

Regulation of Feeding by Somatostatin Neurons in the Tuberal Nucleus (Science 6 JULY 2018: Vol 361, Issue 6397)

URL: //www.sciencemag.org/content/361/6397/76

References:

1. White, L. E., & Hain, R. F. Anorexia in association with a destructive lesion of the hypothalamus. Arch Pathol 68, 275-281 (1959).

2. Kamalian, N., Keesey, R. E., & ZuRhein, G. M. Lateral hypothalamic demyelination and cachexia in a case of malignant multiple sclerosis. Neurology 25, 25-30 (1975).

3. Margules, D. L., & Olds, J. Identical feeding and rewarding systems in the lateral hypothalamus of rats. Science 135, 374-375 (1962).

4. Hoebel, B. G., & Teitelbaum, P. Hypothalamic control of feeding and self-stimulation. Science135, 375-377 (1962).

5. Shutter, J. R. et al. Hypothalamic expression of ART, a novel gene related to agouti, is up-regulated in obese and diabetic mutant mice. Genes Dev 11, 593-602 (1997).

6. Ollmann, M. M. et al. Antagonism of central melanocortin receptors in vitro and in vivo by agouti-related protein. Science 278, 135-138 (1997).

7. Aponte, Y., Atasoy, D., & Sternson, S. M. AGRP neurons are sufficient to orchestrate feeding behavior rapidly and without training. Nat Neurosci 14, 351-355 (2011).

8. Luquet, S., Perez, F. A., Hnasko, T. S., & Palmiter, R. D. NPY/AgRP neurons are essential for feeding in adult mice but can be ablated in neonates. Science 310, 683-685 (2005).

9. Zhang, X., & van den Pol, A. N. Rapid binge-like eating and body weight gain driven by zona incerta GABA neuron activation. Science 356, 853-859 (2017).

10. Clark, W. E. L. G. B. J., Riddoch, G., & Dott, N.M. The hypothalamus, morphological, functional, clinical and surgical aspects. The Henderson trust lectures. nos. XIII-XVI (William Ramsay Henderson trust by Oliver and Boyd, Edinburgh, London, 1938).

11. Kremer, H. P. The hypothalamic lateral tuberal nucleus: normal anatomy and changes in neurological diseases. Prog Brain Res 93, 249-261 (1992).

12. Timmers, H. J., Swaab, D. F., van de Nes, J. A., Kremer, H. P. Somatostatin 1-12 immunoreactivity is decreased in the hypothalamic lateral tuberal nucleus of Huntington's disease patients. Brain Res 728, 141-148 (1996).

13. Kremer, H. P., Roos, R. A., Dingjan, G., Marani, E., & Bots, G. T. Atrophy of the hypothalamic lateral tuberal nucleus in Huntington's disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 49, 371-382 (1990).

14. Lewin, K., Mattingly, D., & Millis, R. R. Anorexia nervosa associated with hypothalamic tumour. Br Med J 2, 629-630 (1972).